I'm not a wine critic or a winemaker. As a chemical engineering student, most of my time is spent in a materials science lab, where I work with surfactants and strange forms of silica. Even back when I did study yeast, I was more interested in genomic analysis than the bouquet of their by-products. In my spare moments, though, I can inevitably be found with my nose buried in a wine glass or a book about wine.

I first became interested in wine after sampling a few bottles with friends on my 21st birthday. I was, and still am intrigued by this ancient liquid's unpredictability. It's nearly impossible to know what aromas and flavors the next glass holds, no matter how much you have read about the producer, region, vintage, and cuvée. A bottle of wine can transform dramatically over years, and a glass of wine can change with equal guile over minutes. It's a scientist's nightmare, a substance that cannot be categorized or classified with any certainty, and yet there is information in each glass - wines can speak unerringly of terroir, vintage, and varietal. Scent, and its inseparable counterpart, taste, is the most primal and intuitive of senses, and the most strongly linked to memory. A single sip can transport you to a memorable dinner several years ago. Yet romantic and ephemeral as wine can be, it is ultimately a real substance, made up of identifiable molecular species. What can science tell us about tasting wine?

First, let's examine our sense of smell. The human nose is like a vast array of unique keyholes, and each scent molecule is a key. When the key matches with the keyhole (in reality a complex protein receptor), a nerve sends a signal to your brain that says "cloves" or "green pepper," identifying the scent. As the analogy implies, our sense of smell is incredibly accurate at the molecular level. A classic example is the pair of molecules S-carvone and R-carvone, which are perfect mirror images of each other, yet the first smells of caraway and the second of spearmint. There are exceptions - we can be fooled by similarly-shaped molecules, and we sometimes register several molecules in combination as a single scent - but for the most part, smell is highly specific.

In other words, when you smell apricot in the glass, it's probably because there is a substance in apricot that is also in the wine. There are hundreds, perhaps thousands, of different substances that can be produced by our complex little fungiform friends known as wine yeasts, and scientists have not yet isolated and identified all of them, so the next time you smell something strange in a wine, like black pepper or capsicum, know that it's not just your imagination.

Conversely, don't turn your nose up at a fellow taster who seems to smell something that no one else does. We've all been at tastings where everyone likes a certain wine except one person, who claims it smells corked, or oxidized. That taster is probably right. Everyone has different thresholds for different scent molecules, and these can vary widely. Below this threshold you cannot detect the substance. In the key-and-lock analogy, some keyholes are rustier than others, preventing the keys from getting in easily, and your friend may have different set of rusty keyholes than you do. When only one person in a group perceives the wine as being corked, reason suggests the TCA level is just below everyone else's threshold. With practice, you will develop a good idea of how your thresholds for different substances compare to your friends'.

Threshold variation is largely genetic, and highly variable. Combine this with simple thermodynamics, and we can understand that swirling the wine and swishing it around in one's mouth during tasting change the flavor profile you perceive. Let's back up: When you swirl wine, you increase the population of aroma molecules in the air above the liquid surface. Some aromas you could not perceive before are now above your threshold. Other aromas that you detected before swirling have become more intense, or have become masked by secondary scents. Similarly, when you aerate the wine in your mouth, you warm it and form a temporary emulsion with air – again, increasing the gas-phase concentration of aroma molecules. You perceive a different "picture" of the wine than from the glass.

What does this science mean? First, wine is complicated. What you taste depends as much on yourself as on the wine. Second, if you do the simple swirl, sniff, and swallow that so many "wine educators" recommend (see the Wine Spectator's how-to videos), you only see one side of the wine. It's like looking at a sculpture from the front, without seeing its other sides. To see the full 360 degrees of the wine, you need to sniff softly, sniff deeply, sniff when the wine is still, sniff after swirling, aerate the wine in your mouth, swish it around, then make sure you exhale after spitting or swallowing to observe the retronasal finish. The dainty taster who delicately sniffs Lafite from four inches above the glass might as well peer at a Picasso through a pinhole.

Far from demystifying wine, science provides remarkable insight as to the depth and extent of wine's complexities. It reassures us that our often rhapsodic tasting notes have validity. It tells us to have confidence in what we smell, even if no one else smells it. It disabuses us of the notion that we must be delicate and proper when tasting wine. Thermodynamics can tell us why wine changes in the glass, if not precisely how. Gas chromatography can identify hundreds of aroma compounds that appear regularly in wine, but cannot match them precisely to the organoleptic phenomena of smell. Wine lovers can learn something from science, true, but perhaps scientists could also learn a thing or two from wine.

... Read more.

Wednesday, September 24, 2008

An Engineer Tastes Wine

Saturday, August 30, 2008

The Scholium Project: 2007 'Naucratis' (Lost Slough Vineyard)

In the past few weeks, I've stumbled across wines from two wine makers whose approaches are so original, and deliberate, that they immediately captured my attention. As luck would have it, I found the last bottle of Sean Thackrey's Pleiades XV in the Corkscrew, and it now sits on my shelf, awaiting sufficient courage to open it. Even though it's the largest production of all the wines produced by that medieval tinkerer, it's not easy to find.

In the past few weeks, I've stumbled across wines from two wine makers whose approaches are so original, and deliberate, that they immediately captured my attention. As luck would have it, I found the last bottle of Sean Thackrey's Pleiades XV in the Corkscrew, and it now sits on my shelf, awaiting sufficient courage to open it. Even though it's the largest production of all the wines produced by that medieval tinkerer, it's not easy to find.

I was floored when I saw The Scholium Project '07 Naucratis at the new CoolVines store. Apart from Abe Schoener's extraordinary philosophy (which seems to make so much more sense than everyone elses), there were only 275 cases of this wine produced! At $5 below the winery's own price, this was a no-brainer.

Schoener is known for making unique wines from small vineyards. So what? Doesn't everyone these days? But there's something compelling about Schoener's eloquently-written credo. After reading it, one can't help but admire his aim: to display the excellence inherent in the vineyard, rather than use it as an ingredient. Of course the particular way in which he displays this excellence is quite original. Perhaps in aiming for flavor ripeness, not Brix, and long macerations he produces interesting wines, that communicate secondary flavors with clarity, but also sometimes result in huge, alcoholic beasts that many people can't stand.

I was sold at "small-production", "vineyard-driven", and "unique", but when I also greatly respect Schoener's unabashed extremeness. Wine isn't all balance, balance, balance as the dusty old British writers say. Rather, wine (as life) is a balance between balance and extremes. Read it over again, I'm fairly sure it makes sense. With that in mind, I was more than eager to try this wine, which did not disappoint:

The Scholium Project 2007 Naucratis, Lost Slough Vineyard (100% Verdelho).

Pale green straw in the glass, this wine has a beautifully expressive (if not high intensity) nose of honeysuckle, papaya, cool stones, and traces of grass, genmai, smoke, straw, and lime. In the mouth it offers up sweet, luscious, beautiful fruit with medium-to-full body and gorgeously soft texture. Undeniably delicious, with excellent acidity, the fruit lasts over 30 seconds on the finish. The flavors are well-integrated and harmonious, and it's so damn yummy I'm smacking my fist on the table repeatedly. The alcohol fumes burn my nasal membranes, and it's definitely hot in the mouth (14.9%), but you know what? I don't care.

Score: 88-92 points.

Availability: Only 275 cases were made. $22.50 at CoolVines.

Food pairing: I would like to drink this with a plain baguette and a hard, salty cheese, perhaps piave, or even some saltier bleu cheeses, like Roquefort.

Tasting conditions: I tasted at room temperature, as I taste all whites. Glasses: Riedel Bdx, Ravenscroft Impitoyable.

Conflict of interest: I think CoolVines is a cool new store. No I'm not being paid to advertise for them. I do think they have a great deal on this particular wine, though.

... Read more.

Thursday, August 28, 2008

The new kid on the block!

It's definitely a happy day for wine lovers in the Princeton area. The wine store CoolVines just completed it's first week in it's new location, on Harrison and Nassau. Here's the rundown:

The location is a bit out-of-the-way for students. In particular, it is not within easy walking distance of the Palmer Square/Witherspoon St. area. On the other hand, it is within range of the Blue Point Grill, which is probably the best BYO within reach of student budgets.

The design of the store is elegant and innovative, if a little cramped. Wines are organized by color, body (light-med-full), and price (the cheapest wines are at the bottom, so bring kneepads!). The island at the center of the store functions both as a register and a tasting station, during in-store events.

Their selection needs a bit of work, as they themselves will admit. Currently it seems to be about 1/6th the size of the Corkscrew's. I'll be honest - I hadn't heard of a single wine on their shelves, but the first wine I purchased (a Chinon) was a solid selection. Perhaps their under-the-radar-wines approach is a good thing. They also have selections from New Zealand, Australia, South America, and South Africa - none of which are represented at the Corkscrew.

Their beer selection is already one of the most exciting shelves of alcohol in any store in town. I saw Dogfish Head, Stone, and a bunch of lambics that I will certainly be back for. In addition the spirits section is getting an overhaul, since Eric Mihan is on board. For those of you who didn't shop regularly at the Corkscrew, Eric is a spirits specialist, but also knows his stuff when it comes to wine. He's the go-to guy for cheese pairings, as he used to run Whole Foods' cheese counter.

The best thing about CoolVines is that they have seen what the Corkscrew has failed to acknowledge, and what California wineries have known all along: tastings, tastings, tastings! CoolVines offers free in-store tastings every Wednesday (5-8) and Saturday (2-5). The glasses are little sherry copitas that are oh-so-cute! In contrast, the Corkscrew hasn't had a tasting for months.

Furthermore, CoolVines offers a wide range of services that the Corkscrew doesn't, including wine service at BYO restaurants. While I doubt many students will be taking advantage of that, the wealthier members of the community will find it convenient.

To sum up: Check out CoolVines, but don't abandon the Corkscrew just yet. Mr. Chapuis is definitely the man for France (that is, anti-Parker France), and his French selection is an order-of-magnitude more extensive than CoolVines. For wine geeks who are used to browsing by region, the Corkscrew's layout is probably less of a headache than the CoolVines layout. However CoolVines is more friendly to those of us who haven't memorized thousands of obscure French AOC's, and want to pick up something that will go well with dinner the same night. Plus the people there are cool.

... Read more.

Wednesday, August 13, 2008

It's not all subjective!

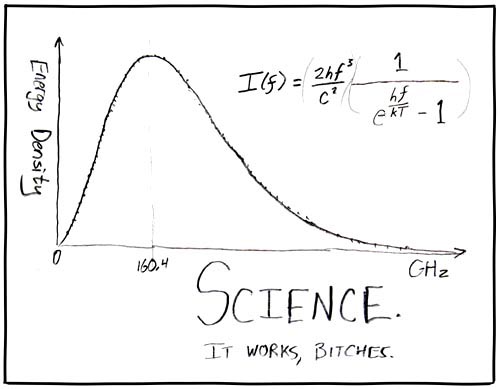

Early on in my wine drinking career, I was convinced that the evaluation of wine could be completely objective. I brandished Robert Parker's 100-point system like a golden cross. My good friend Liz argued vehemently that the evaluation of wine is completely subjective, and can't be reduced to anything as mathematical and clinical as scores. As I learned more about wine I realized she was partly right - it is impossible to remove the subjective element from wine tasting. On the other hand, there is objectivity to be found, as shown by the following diagram:

So, Liz, I'm not insane after all... at least not completely!

... Read more.

Monday, August 11, 2008

What is a winemaker?

As the singular vintner-rebel Sean Thackrey is fond of pointing out, there is no word in the French language for "winemaker." The word used instead, vigneron, means "wine-grower", but it connotes vinification as well (Rosenthal, memoirs). Paul Draper, the wine-maker/philosopher in charge of Ridge, asserts that wine is "grown, not made." Who, then, is a wine-maker?

Perhaps, he (or she) is one who through a quixotic mixture of love and harsh upbringing, coaxes the subtleties of terroir out of his grapes. His duty during vinification is to quite simply get out of nature's way.

Perhaps he is one who imposes his own personality on the grapes, resulting in a duel, or a duet of vintner vs. nature. His wines always have a bit of himself in them.

Perhaps he is a skilled artisan, removing all flaws, then standing aside to let Nature take care of the rest. His wine is different from year to year, as nature is different from year to year.

Perhaps he is a slave to the vine, giving up long hours for the opportunity to drink some of his own wine with good friends.

Perhaps he is a visionary, seeking to change the world of vinification. He knows where winemaking comes from, and wants to take it to a new place.

The few winemakers I've met were humble and extremely friendly. They value the growing of good grapes above all, and love to share their great works with friends. I hope to meet many more over the course of my life, and perhaps I will come closer to an answer in the future. At present, I have none.

... Read more.

Monday, July 28, 2008

Working for Paul Romero: Part 2

On Saturday I worked at the newly-planted Sesson Vineyard (Santa Clara Valley AVA), with Paul's vineyard construction manager, Millie. An electrician by trade, Millie is as practical and tough as the irrigation lines she showed me how to string. As we were stringing the beginnings of a 5-wire trellis, and attaching black drip-lines to the lowest wire, she waxed eloquent about the clay soil, irrigation, killing gophers, and canopy management, occasionally pausing for a puff on a cigarrette.

On Saturday I worked at the newly-planted Sesson Vineyard (Santa Clara Valley AVA), with Paul's vineyard construction manager, Millie. An electrician by trade, Millie is as practical and tough as the irrigation lines she showed me how to string. As we were stringing the beginnings of a 5-wire trellis, and attaching black drip-lines to the lowest wire, she waxed eloquent about the clay soil, irrigation, killing gophers, and canopy management, occasionally pausing for a puff on a cigarrette.

A bit past noon, we ran out of plastic ties - time for a Home Depot run! We got into her boxy black jeep ("A bit rough, but it gets the job done - like me!") and I recieved an impromptu seminar on the art of growing good grapes.

Growing mediocre grapes is easy, but to grow grapes with any semblance of flavor concentration means severely slashing yields, taking only the primary fruit, reducing the tonnage per acre. It's not the most intuitive business model. "You gotta be crazy to grow good grapes" she said, "and if you grow bad grapes, people know - you taste the grapes and you just know. There's no hiding." How much do good grapes cost in Santa Clara? A couple grand per ton. In Napa/Sonoma? You can pay $5k and get crap.

On our way back from Home Depot, we stopped by Sycamore Creek so I could see what head-trained vines looked like. They instantly called to mind photographs I'd seen of Graves, in Bordeaux - lonely looking, beautifully gnarled trees, like bonsai in a desert. Clearly well-cared for, pristine.

We tasted through their releases and I noted that all the wines had great balance and acidity. The pinot was light, flavorful, and earthy. The other reds were quite dry, and not overly alcoholic. All across the board, each wine had several different flavors that it communicated with clarity. They were enjoyable and interesting to taste through, and I wish I'd had more time there to really write down complete impressions.

Afterwards we checked out Uvas Creek vineyards - the best grapes in town, according to Millie. Bill is a dirt farmer, so he keeps his rows clean and tilled. As a result he has to do more pruning work than most to keep the vigor down. The vertically trained vines were simply gorgeous - every leaf seemed in its proper place, and the view down each long, perfect row was stunning. Sensing my awe, Millie commented "Bill himself is in the vineyards every day - he checks every grape and removes the bad ones" - sure enough, we met him on our way out.

Bill Holt seemed to me the iconic image of a California farmer - Large-framed, a simple straw hat shading a sun-creased face, with a grizzled white beard, an easy smile, and a bone-crushing handshake. He wore an impeccable collared shirt, sleeves rolled, and at the same time had the vineyard's dark clay soil under his fingernails. He spoke slowly, wryly, his imagery incredibly old-fashioned ("that juice from the petite verdot was black as your hair!"). And at the same time he spoke of complex lab tests, chromatography results- modern ways of quantifying flavor ripeness that, he made clear, are only to be used in conjunction with tasting the berries. Millie amicably berated him for not having enough grapes to give to Paul this vintage.

If there's one thing I learned today, it is that Paul Draper is right - wine is grown, not made. The French term for winemaker is vigneron, which means literally "one who grows vines." Great wine is made in the field, one berry at a time, and then the vintner tries not to mess it up during vinification.

Here are my specific notes:

Vigor:

The idea of reducing vigor is fundamental to winemaking. For example, hillside vineyards are prized because they add stress to the grapes by retaining less water, decreasing the vigor. Pruning to decrease vigor is crucial. Dropping fruit is crucial to reduce production - usually you only want the primary fruit. As I understand it, vigor refers to vine growth/shooting laterals, and production refers to grape growth. Old vines produce small quantities of small berries - low vigor and low production which leads to high flavor concentration.

Irrigation:

The vines at Sesson had been newly plante (grafted?) a few months ago. We strung a wire low across each row, and then fastened the irrigation pipe to the wire with plastic ties. Millie thinks the owners made a mistake with irrigation as all the 20-odd rows are fed by one line. They should have run a separate line for every three rows, from the main water source. From a fluid mechanics point of view, I think they will have severe trouble with pressure drop at the end of the field. Irrigation, however, is not in Paul's/Millie's job description.

Watering:

Over-watering causes lots of fruit production, with big, watery grapes, and lots of vigor ("the grapes look woolly"). A telltale sign is an abnormally large distance (maybe a foot instead of 4 inches) between laterals. After the Sesson vines are mature and grape-producing, they'll rarely be watered at all - instead, their roots should go deep enough to access the water table. Since Sesson is on agri-designated land, they'll get lots of cheap water that they can then use to water their lawn/garden, since the vines eventually won't need it.

Rabbits/deer:

Sesson is too exposed for rabbits - the birds of prey will eat them. When the vines are bigger, the rabbits will have shelter from eagles/hawks, but by then the trunks will be so thick that the rabbits will only be able to eat the suckers - which actually saves work. Deer don't seem to be a problem in this particular area, but there are many ways of dealing with them - fences, strong-smelling wards, etc.

Gophers:

Gophers tunnel around and poke holes up for air. They eat roots, killing the vines. One way to combat them is to poke around with a re-bar until you find the tunnel (the bar sinks easily into the ground), dig up the tunnel system and put poison there, covering the hole with a brick. The gopher will try to re-dig the airhole, and in doing so will eat the poison. This is not a good idea if you have cats/dogs, as they could eat the poisoned gopher. Alternatively, you can trap it - but this is only possible if you are around the vineyard often, as you need to kill the gopher once trapped. The simplest method is to find a hole and flood it out, then hit it on the head with a shovel.

Canopy management:

In vertical training, the main stem splits into two laterals that go along the lowest trellis wire (above the irrigation wire). These produce the "primary fruit." At each junction on these laterals, 2 vines shoot upwards, bearing secondary fruit, which should be dropped. These secondary laterals are used just for photosynthesis and shade control. The region between the second and third wires above the ground is called the "fruit zone." For ease in tucking, the upper wires can be slackened until the vines grow well past the fruit zone, then tightened, saving time and effort in tucking stray shoots.

In head training, the main stem splits into several secondary stems, growing upwards like a small tree against a single vertical trellis. Until the main stem is sturdy enough to support the whole plant, a single vertical post is used as a trellis, and the secondary stems are tied to the top of the post. This is known as "basket training." Head training is more work than vertical training, and requires careful pruning. It is said to be good for Zinfandel, as it keeps the vigor/production down - the plant naturally scales back production to avoid collapsing from excess fruit. Head training is widely used in the Rhone valley.

We stopped by Sycamore Creek so I could see what head-trained vines looked like - they instantly reminded me of some photographs I'd seen of Graves - lonely looking, beautifully gnarled trees, like bonsai in a desert. Clearly well-cared for, pristine. The earth at Sycamore creek was light brown and dusty/crumbly. Not black and hard like the clay at sesson. Chaine d'Or seemed to have similar earth. The vineyard topography was flat.

In both types of training, a delicate balance must be found. Leaving too few leaves limits the nutrients to the grapes, and hence the flavor development suffers. Leaving too many leaves can make the bunches susceptible to mildew, as they don't get enough sun and air.

Weeds:

There are two schools of thought: Bill Holt, of the dirt farmer mentality, tills the ground in between the vines. He has to work extra hard to keep down the vigor. Millie and Paul believe in letting some weeds and some specially chosen ground cover aid in keeping the vigor low.

Grape pricing in different AVA's:

Santa Clara Valley AVA grapes go for a couple thousand dollars per ton. Santa Cruz would be a thousand more, perhaps $3500. Napa/Sonoma goes around $5000 at the low end, and they might not even be good, you have to taste them and find out how the vines were cared for.

Meeting Bill:

Bill Holt grows the best grapes in town, according to Millie. Paul made a very successful cabernet from Uvas Creek in '05, but didn't get any grapes this year. Bill tastes his grapes but also sends them to a lab to measure anthocyanins, tannins, and other species to quantify ripeness. He also grows Petit Verdot, which seems to be in high demand recently. He said the anthocyanins (which are factors in color, flavor, and mouthfeel) were so high that the petite verdot grapes were almost black during press.

One of the wines I tasted at Sycamore Creek was an '05 Cab made from Bill's Uvas Creek grapes - the same harvest that Paul at Stefania used for his well-recieved '05 Uvas Creek Cabernet, though Paul used 50:50 Clone 4 and Clone 337, and Sycamore Creek used 100% Clone 4. In the mouth the wine was light, yet intense in flavor, with a medium-soft tannic grip that was very smooth, even plush in texture. There was a little earth on the nose, with good fruit and hints of tobacco. The balance and acidity were excellent. I don't know how representative this winery is of the area, but I liked the wines a lot. They were not too fruit-forward, sweet, and oaky, which Millie says can be a problem in Napa wines. I can't wait to try Paul's wine from the same grapes!

... Read more.

Sunday, July 27, 2008

Mystery Wines!

Ex-sommelier, wine guru, and teacher extraordinaire Joe G recently led a series of blind-tasting challenges on the WLTV forums. Here are links to the Mystery Wine threads. Read his initial post and try to guess based on flavor descriptors what the wines are! Joe's advice: reasoning is more important than getting it right. Not all wines are typical of their region/varietal. Joe coached us through the wines, giving hints and analyzing our responses, eventually revealing the wine.

Mystery Wine 1

Mystery Wine 2

Mystery Wine 3

Mystery Wine 4

Mystery Wine 5

Mystery Wine 6

Mystery Wine 7

Mystery Wine 8

Mystery Wine 9

Mystery Wine 10

... Read more.